The 2010 After Dark Toronto Horror Film Festival was brought to a close by a screening of the most talked-about horror film of the year. Sitting in the packed Bloor Cinema, a crowd of sick minds braced itself for a lesson in the disgusting, a tutorial on the depraved. Choking on our own mental vomit, festering in our own gut wrenching shock, those of us lucky enough to have a seat in the historic sold-out theater witnessed The Human Centipede (Six & Six, 2010). In this lovely Dutch film, we follow three hapless tourists as they are kidnapped by a deranged German surgeon who is determined to create the world's first siamese triplet. By surgically connecting the helpless victims, mouth to anus, and training them to perform depraved acts -- including fetching his morning newspaper from the front lawn -- the surgeon proves his creative genius and relishes in his over-nourished vanity. Enough said.

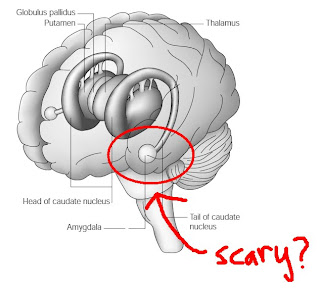

The hype generated by this film is proportionate to its ability to shock and disgust. The thought of the deranged doctor's siamesse triplet, for very primal and visceral reasons, is excruciating torture for anyone who has an ounce of dignity and a pound of self preservation. As you might be able to guess, this movie capitalizes on at least one very basic aversion. Indeed, the aversion to human feces appears to develop quite readily in infancy. Brain structures such as the insula (a cortical region tucked deep within the temporal lobe; see Calder et al., 2000) seem to be critical for interpreting and experiencing feelings of disgust in response to social signals -- for example, the contorted face of the 'second-position' as she gulps a big load of ---). In The Human Centipede there is no shortage of opportunities to exercise the insula's response to these social signals of disgust, and, quite frankly, we feel that this film could serve as the basis for a neuropsychological test designed to probe this brain region's activity.

Check out The Human Centipede at:

References

Calder, AJ., Keane, J., Manes, F., Antoun, N., & Young, AW. (2000). Impaired recognition and experience of disgust following brain injury. Nature Neurosceince, 3, 11, 1077-1078.

Six, T., & Six, I. (Producers), Six, T. (Director). (2010). The Huamn Centipede [Motion picture]. Netherlands: IFC Films.